|

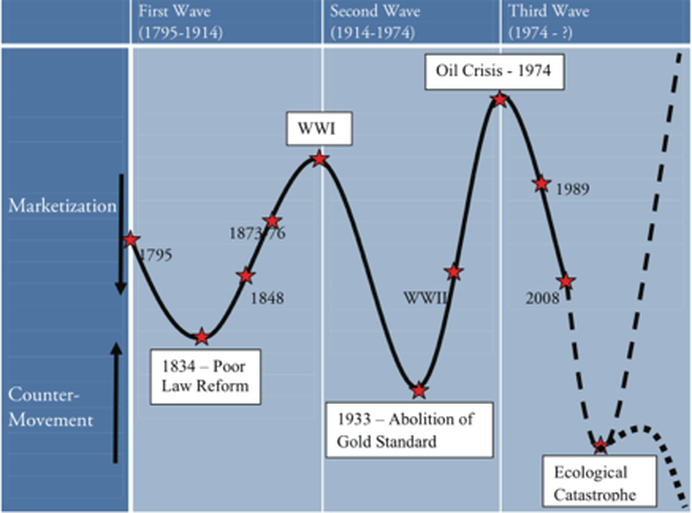

Abel B.S. Gaiya, A student of Christian apologetics and social theology  (Credit: Yuttana, Contributor Studio, Shutterstock) (Credit: Yuttana, Contributor Studio, Shutterstock) Walt Rostow (1959) infamously put forth a five-stage theory of economic development, extrapolating from the experiences of the great industrialized nations. However, as dependency theories strongly pointed out, the conditions under which those countries industrialized is significantly different from those that prevailed after decolonization. In addition to this, democratic capitalism experiences turbulence, which I argue makes development under this global system a struggle against powers and against what I call “Burawoyan Cycles”. Late Development as a Battle Late development is a battle with foreign powers (core-periphery relations). Dependency theorists’ argument that late development occurs under a different set of conditions is contrary to those who directly extrapolate from the industrialization experiences of the early industrializers. This is why the term “late development” is a misnomer, as it implies only a temporal difference, and not a structural difference between the conditions of early development and those of late development. Particularly, colonialism, which structured colonies to serve an extractive purpose, integrated late developers into the global economic system in a very specific manner, and locked them into an asymmetric international division of labour (under which the opportunities for expanding technological capabilities and for inclusive and equitable development are internationally asymmetric). This core-periphery structure largely persisted even after decolonization, more so because many of these countries never received their own Marshall Plan, given that large financial and technological requirements are particularly intense for late-comers (Fischer, 2009:858). The Bandung conference, the Doha gridlock, World Bank voting rights tussles, are all manifestations of the developmental struggle against foreign powers. Nonetheless, as László Bruszt (quoted in Kvangraven, 2017) argues, different countries operate under different dependency conditions, and hence some developing countries face less international constraints to development than others. Furthermore, although a hegemon typically enforces the international economic order, it is not omniscient and omnipresent; and therefore countries have some leeway to exploit gaps in the international governance system. In addition, regional and country-specific factors (such as institutions) are also important, especially to explain variation in growth performance across countries facing similar international constraints (Ocampo and Parra, 2007:74-75). Therefore the notion of dependency does not extricate countries from their internal responsibilities. Late development is a battle between capitalists and the state (state-capital relations). Developmental state theories have been called the “only realistic alternative to free-market development” (Chang, 2013:86). Yet Vivek Chibber (2009) argues that the developmental state is highly vulnerable to perversion by capitalists who seek to squeeze out all the benefits of state protection and aid, while avoiding the expectation of building national competitiveness. This means that the developmental state is always mired in a struggle to balance the need to coordinate with the business class, with the need to enforce the public will upon this class without being co-opted. Late development is a battle between society and political and bureaucratic elites (state-society relations). The experience of colonialism disallowed an organic development of governments and politics within the developing world. Moreover, a poorly-developed private sector, gray-area political systems (Carothers, 2000), bureaucratic capacity constraints, and several other problems breed many misdirected and corrupt political and bureaucratic elites (Cooper, 2002). Therefore, both the mass public (including civil society) and the developmentally-oriented leaders have to consider the interests of those elites who wield significant power but engage in anti-developmental activities to gain rents, as the political settlements approach argues (Khan, 2010). In addition, the state itself may be both politically repressive and developmentally deficient – in which case there is a perpetual battle between civil society and the state. Finally, late development is a battle between labour and the state (state-labour relations). Late development also involves balancing the interests of organized labour to increase wages with the need for wage restraint if undergoing export-led or export-oriented industrialization. Typically, developmental states have been repressive of labour (Chang, 2009); but labour liberation may be needed to foster “internal integration” (Wade, 2003:635) in order to enable the growth of domestic demand in the long-run. A Marxist-Polanyian Analysis: Development and Cycles Michael Burawoy (2010), in combining Karl Polanyi’s theory of the double movement, and the Marxist theory of crisis, proposes that capitalism “alternates between crises of legitimation and crises of overaccumulation” – a phenomenon which I call “Burawoyan cycles”. The golden age of capitalism was undergirded by the triumph of social democracy (Sherman, 2006) as leaders and thinkers, learning from the experiences of the Great Depression and World Wars, widely agreed on the destructiveness of unfettered markets, and that unregulated markets produce countermovements that challenge capitalism’s legitimacy (as fascism, communism and national socialism did). They tried to “re-embed” capitalism into society and subject the market to the forces of democracy and coordination. However, the crisis of overaccumulation (Robert Brenner, 2006) that struck the industrialized world from the 1970s, disrupted this age of “embedded liberalism” (Ruggie, 1988) and thus led to a break from the social democratic and Keynesian consensus and back to marketization, liberalization and deregulation. Ocampo and Parra (2007:65-68) posit a “global development cycle” (GDC) as an explanation for the stylized fact that during the golden age of capitalism (1950-1973) growth was fairly widespread in the developing world (with some convergence of real incomes vis-à-vis the industrial world occurring in 1965-1973); whereas from 1980 there was a “dual divergence” entailing both lower growth rates of developing vis-à-vis industrial countries, and amongdeveloping countries. They also state that “The outstanding difference between ‘the dual divergence’ and the ‘golden age’ has been the significant increase in the frequency of growth collapses and the much lower frequency of growth successes over the past quarter century (1980-2005)” (p. 71). The GDC is “the average growth performance of developing countries resulting from a set of external factors that affects all or large clusters of them, and thus constraints each country’s growth possibilities” (p. 71). Ocampo and Parra maintain that the “dynamic processes” and “global effects of events originating in developing countries with systemic importance” (p. 71) play the leading role in determining the GDC, and “thus, the end of the ‘golden age’ in industrial countries also marked the end of the ‘golden age’ of development” (p. 73). This means that the global development cycle is a consequence of the Burawoyan cycle. And if the Burawoyan cycle is recursive as Burawoy argues, then it means that late development is a race against these cycles – a permissive global developmental environment will eventually be disrupted by a repressive one. The crisis of overaccumulation which disrupts the pseudo-embedded liberal order leads the overseeing hegemon, in attempting to relieve the pressures, to intensify the international division of labour (which, implies that dependency is not only cross-nationally heterogenous, but also varies inter-temporally) through imposed liberalization across the developing world; and this reduces international income mobility. Since the third wave of marketization from 1974 is the latest wave of the cycle, it is expected that the counter-movements gradually gain ascendancy as global capitalism passes through a crisis of legitimation. Dani Rodrik (2012) has warned of a “globalization dilemma”, whereby globalization is increasing demand for social protection within nations, yet at the same time undermining the capacity of governments to supply it. Therefore capitalism is vulnerable to backlashes around the world, which will intensify if no grand compromise is established. Signs of the incipient crisis of legitimation are already visible, from the ascendance of Trump and Sanders, to Brexit, and the general rise of populism around the world. Counter-movements against markets arose even from the 1980s, but they saw an acceleration after 2008. Fascism, communism and National Socialism intensified in the 1930s because of depressed economic conditions, and the world experienced the breakdown of the world order. With another significant global economic shock, the present populist counter-movements which challenge both markets and American hegemony will gather pace, and another period of global political turbulence is likely to be seen. Just as the World passed through turbulent times in the first half of the 20th century before a grand compromise was struck, a new bout of global turbulence may be experienced (albeit in different form) before a new grand compromise which reverses or at least halts the “shrinking development space” (Wade, 2003). This is especially so given that within the Marxist theory of overaccumulation, the mass destruction of capital which relieves the crisis of profitability, is what revitalizes the system (Boyle, 2016:30), and is why the golden age of capitalism was viable – because it came at the heel of a world war and a Great Depression which were characterized by mass destructions of capital. There are two trends that add to the race-nature of late development under capitalism. The first is climate change. In Burawoy’s heuristic model, “each successive wave of marketization is characterized by a new combination of fictitious commodities” (p. 308). And in the third wave (1974 till present), it is the articulation of the commodification of labour, money and nature, with the commodification of nature expected to ultimately take the lead. With climate change as a global challenge, the countermovement against the third wave of marketization must also be global. Yet the asymmetry of power combined with the necessity to incur “immediate sacrifices for long term and uncertain gains” (p. 311) in order to avert or minimize ecological disaster may lead to a new pseudo-embedded liberal order in which there are greater constraints put upon the developing world to develop. Therefore, with the challenge of climate change, it may mean that with each successive Burawoyan cycle, global development constraints get tighter. Indeed, Burawoy mentions that marketization (which, even under embedded liberalism still exists, albeit less intensively) is characterized by short time horizons, which is inimical to the long-term horizons and short-term sacrifices needed to tackle climate change. Therefore, “Perhaps long time horizons can only be imposed by authoritarian rule…” (p. 311). Given that a “stable” global authoritarianism implies hegemonic authoritarianism (Hegemonic Stability Theory), this means that the future hegemon, if humanity takes this course of possibility, may be more imposing of international economic rules which further lock-in the international division of labour. Late development is therefore a race against this future occurrence. The second trend is technological change. According to the World Bank (2016:23) estimates, two-thirds of the current labour force of developing countries is vulnerable to automation. As Hallward-Driemeier and Nayyar (2018:1) mention, “These trends raise fears that manufacturing will no longer offer an accessible pathway for low-income countries to develop and, even if feasible, would no longer provide the same dual benefits of productivity gains and job creation for unskilled labor.” Therefore, late development is also a race against the intensification of this challenge. Rodrik (2015) already demonstrates that “premature deindustrialization” on a global scale is becoming an issue. He argues that although “For countries that still remain mired in poverty, such as those in sub–Saharan Africa, future economic hopes rest in large part on fostering new manufacturing industries” (p. 1), industrialization opportunities are declining for countries sooner and at lower levels of income compared to the experience of early industrializers (p. 15). Looking Ahead: Radical New Solutions Required The developing world is indeed facing a future of increased turbulence of incredible proportions. Capitalism is a relatively young economic system, and the challenge of late development, proper, only emerged in 1945, under a historically unprecedented American-led liberal world order. The ecological crisis and technological change that we now expect to face is also historically distinct. We cannot simply look to the past industrial revolutions and say we have nothing to worry about, because this one is distinct (Martin Ford, 2015). A global grand bargain, if it is to be beneficial for the developing world, requires large sacrifices to be made by the developed world (just as the post-war developmental concessions to Western Europe, Japan and South Korea were large sacrifices made by the U.S.). This means that we can expect significant conflict over any negotiations for a new international economic architecture. And because power plays a key role, the developing world must mobilize effectively. The time scale by which we speak is that of decades; therefore a new generation of thinkers and leaders is needed to foresee these challenges, to mobilize against them, and to construct new solutions. About the Author Abel B.S. Gaiya is a Commonwealth Shared Scholar and MSc Development Economics candidate at SOAS, University of London. This article first appeared in Developing Economics

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

Copyright © 2023 The Zambakari Advisory - Privacy Policy

Our site uses cookies to improve your experience. You can control cookies by adjusting your browser or device settings.

If you continue without changing your settings, we assume that you are happy to receive all cookies.

If not, please feel free to opt out here.

SEO by Qasim Khilji

Our site uses cookies to improve your experience. You can control cookies by adjusting your browser or device settings.

If you continue without changing your settings, we assume that you are happy to receive all cookies.

If not, please feel free to opt out here.

SEO by Qasim Khilji