|

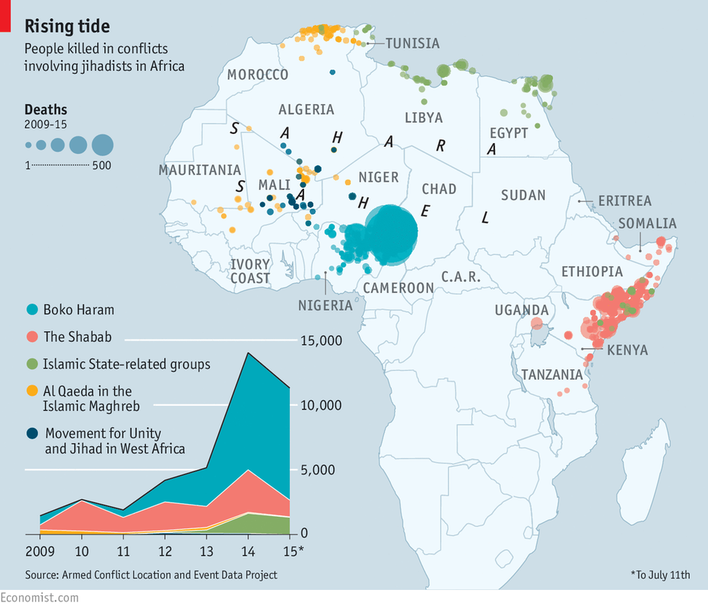

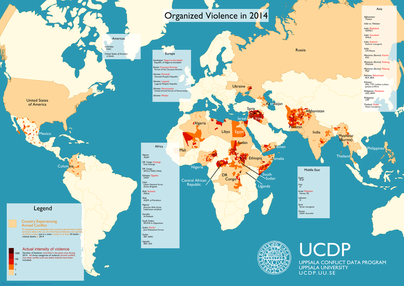

Muhammad Dan Suleiman, University of Western Australia, Perth  Introduction: In recent years, West Africa has come into the global spotlight due to the prevalence of famines, religious terrorism, anti-state rebellions, and arms, drugs and human trafficking. These developments are the product of both local and global dynamics and they remain substantial challenges for the region in 2017 and beyond. There have been positive developments, including an emerging consolidation of support for democratic transitions of power through both popular protests and elite-led regional diplomatic and military interventions against unconstitutional changes of government or attempted unlawful retentions of power. While there are positive developments, concerns have increased of late about insecurity in West Africa in an era of violent criminal and political movements operating across borders. Indeed, West Africa suffers from ethno-religious tensions, political instability, poverty and natural disasters. West Africa is a vast sub-region. Nevertheless, I offer below a highlight of key developments and events to watch in a few countries and locations in the sub-region, and the best way to address pressing issues. Mauritania Mauritania, with a population of 3.2 million, is largely comprised of desert. It had a border dispute with southern neighbour Senegal in 1989, and its northernmost tip goes right into the Maghreb. There are inter-ethnic conflicts (between “Arabised” and black Mauritanians), a history of military coups and the militarisation of governance. While al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has been operating in the surrounding region, Mauritania has largely remained out of the headlines. Yet, despite campaigns to check the infiltration of Islamist extremism into Mauritanian society the threat remains active to the country. Mauritania has several socio-economic conditions that pose risks. Mauritania is one of the traditional routes for the trafficking of drugs between South America and Europe, and is known for kidnapping of foreign nationals for ransom. The country’s military lacks cohesion, which explains the many coup d’états. There are also ethnic rivalries. Governance is weak and clientelistic, with current calls for reform. As a desert country, there are swaths of ungoverned spaces beyond the vigilance of the state. Mauritania has deployed troops to neighbouring Mali as part of the UN’s Multidimensional Integrated Stabilising Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). The aim is to check the spread of militant extremism in the region and insulate its own long border with Mali. While this regionalist gesture is to be applauded, the interplay of the above conditions means that Islamism will remain a threat to Mauritania in 2017 and beyond. Mali With a population of approximately 16 million people and covering 1.25 million square kilometres of land, Mali is a large and landlocked country. Both US and EU policy makers since the 1990s had tagged a democratising Mali as a “bulwark against radical Islam” in West Africa. However, a series of crises since 2012, impacted by the collapse of Gadhafi’s regime in Libya, has seen Mali become one of the frontlines in the battle against violent Jihadism in the Sahelian region. In April 2012, a Tuareg secessionist campaign declared the independence of the state of Azawad in northern Mali. This precipitated political instability and a military coup in the capital Bamako. The resulting chaos was exploited by AQIM, who hijacked the Tuareg rebellion and threatened the forceful takeover of the country while also destroying a number of historically significant sites. A combined French and West African regional military intervention in early 2013 halted the advance and created space for peace negotiations with rebels and national elections. With the election of a new government, and the establishment and deployment of MINUSMA, AQIM fighters and their Tuareg hosts may be dispersed, but not halted. With militants believed to be hiding in hostile terrains in the Sahara, the north of Mali especially the area around Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu remains tense. The Islamist and separatist challenge is still real, with continuing suicide bombings and the presence of an illegal drug trade as signals. So far AQIM’s affiliated Al-Mourabitoun operating in Mali have launched attacks in Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast. With the UN-brokered Algiers Accord failing to grant complete autonomy to Tuareg separatist in the North, a deadly conflation of separatism and Islamism remains an active challenge to the political order in Mali. Indeed, the peace deal, according one analysis, is “one step forward, two steps back”. However, Mali is to be commended for some success in reducing the Islamist threat, and the restoration of the government in the North. The appointment of Iyad Ag Ghaly leader of Ansar Dine as a diplomat to Saudi Arabia is to be welcomed. Such measures to strengthen the government is the surest way to halt any future political unrest. Yet, in a country whose standings in political participation and pluralism, functioning government, and rule of law sit at an abysmal 7 out of 16, 4 out of 12 and 6 out of 16 respectively, the world must watch out for what is next, primarily in the volatile North of the country, but also in central Mali where farmer-herder conflicts are a norm. Nigeria Nigeria, the “Giant of Africa”, is the continent’s most populous state: it produces one of the largest economies and is a regional hegemon. Home to over 300 ethnic groups and 500 languages, Nigeria’s 170 million people occupy an area of 923, 768 square km. Nigeria faces a number of substantial social, economic political and security challenges. These include ongoing violent rebellions against the state, both in the north and the south of the country. Militant religious movements are not new in Nigeria, but the rise in 2009 of the violent Islamist movement Boko Haram has since tested Nigeria’s domestic, regional and global reputation. With the election of President Muhammadu Buhari in 2015, and the regional deployment of anti-Boko Haram forces, the Nigerian governments claims to have “technically” defeated the group by ousting them from their “last” remaining stronghold in Sambisa forest in the north-eastern state of Borno. This joint effort by Nigeria and its regional neighbours is a positive development. Some political stability in Nigeria with the election of Buhari is also a positive development. Still, the question “where is Boko Haram now?” should worry security watchers and government officials. Are the group’s members dispersed in Niger or in Cameroon? Have they reached al Shabaab territory in the East or that of AQIM in the north? Also, in 2017 a rivalry between Abubakar Shekau, Boko Haram’s most popular leader, and Abu Musab al-Barnawi who is claimed to have been appointed by ISIS to replace Shekau could complicate insecurity in the Lake Chad region. This should be closely monitored. Furthermore, should Boko Haram re-emerge elsewhere, what would be the costs? Will Boko Haram continue to use minors in suicide bombings as their new strategy? Answers to these questions should remain actively on the minds of security watchers and governments in West Africa and the Sahel in 2017. Additionally, with the election of Muhammadu Buhari, a northerner and Muslim, there has been a resurgence of secessionist sentiments in the south which has been seen to partly represent southern discontent with the northern president. While militants in the Niger Delta area is an ongoing phenomenon, secessionist campaigns in the Niger Delta may increase and will likely take on a religious and ethnic binary in opposition to the north. Among other threats, Islamism in the north and Secessionism in the south are two issues to watch in Nigeria this year. Senegal Senegal, Africa’s westernmost point, is considered one of the most stable democracies in Africa, with much of the country enjoying relative peace. But in the Casamance region, the Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance (MFDC) has since the early 1980s remained involved in an armed confrontation with the Senegalese government in a campaign for the independence or autonomy of the region. The local conditions in Senegal may militate against the Casamance crisis evolving into a major national and human security threat, but local grievances in the region risks cross pollination with the broader negative security conditions across Senegal’s Sahelian neighbours. This point is strengthened by the seizure of illegal weapons in Lagos meant for the MFDC in 2010. While Senegal’s traditional Sufi Islamic orientation has been a shield against militant Islamist activism, Nigeria offers an example of how the presence of Sufi Islamic traditions is not a barrier to militant extremism. Senegal has also more recently been directly involved in the management of the political crisis in The Gambia, a state which is geographically surrounded by Senegal. After long-time President Yahya Jammeh lost the December 2016 presidential election and refused to cede power, Senegal led a West African regional effort in January 2017 to resolve the crisis by hosting the inauguration of elected president Adama Barrow, and threatening military intervention to install Barrow if Jammeh did not stand down. The threat was successful, resulting in the peaceful transition of power. Senegal gained credit for defending an emerging regional norm strengthening constitutionalism and peaceful elections. This is commendable. But the Casamance is still an issue to watch. Niger Niger is a landlocked country of 1.27 million square km and approximately 20 million people. A key Uranium exporter, Niger is largely arid and comprised of desert. Political instability, chronic food insecurity, and natural crises, notably droughts, floods and locust infestations, have been Niger’s principal challenges over recent decades. More recently, Niger has been drawn in to the Boko Haram insurgency that has emanated from the Lake Chad region and northern Nigeria to its southeast. Boko Haram attacks on Nigerien towns, including Magaria, Jajiri, Diffa and Bosso, has provoked the government in the capital Niamey into the regional anti-Boko Haram military offensive. Although boycotted by the opposition, the 2016 Nigerien elections were conducted in relative peace. The election of Muhamadou Issoufou promises some political stability as the country stays united in response to the threat of terrorism in its south. That said, Niger’s expansive and arid North also remains a challenge due to the presence of AQIM. But Niger’s biggest issues in 2017 may not be terrorism, but how to handle the recurrent issues of drought and famine. Chad A country of around 12 million people covering 1.28 million square km, Chad is another landlocked country through which the Sahel region intersects. Like its neighbours, Chad has been caught up in the diffusion and contagion of Boko Haram in the region. The 2016 Global Terrorism Index (GTI) cited Boko Haram’s regional expansion from Nigeria into Niger, Cameroon and Chad, with a 157% increase in deaths by Boko Haram in these countries. Chad has been a proactive regional leader in counter-Jihadist operations across Sahelian West Africa, including in Mali and the Lake Chad Basin. The Chadian Foreign Minister, Moussa Faki Mahamat, was recently elected as the African Union Commission’s incoming Chairperson for the next four years, a development that may further promote Sahelian security concerns onto the continental organisation’s agenda. But Chad’s political terrain is not a smooth one. The recent conviction of Chad’s former dictator Hissene Habre in Senegal is a victory for justice. The re-election of Idris Deby as President of Chad in 2016 maintains some stability. However, this is Deby’s fourth consecutive term as president, amidst questionable constitutional changes. This is an issue to watch, considering how other leaders, such as Blaise Compaoré of Burkina Faso and recently Jammeh of the Gambia, have attempted to massage the national constitution to extend their stay in power. Additionally, likely that the Boko Haram’s remaining members are on the run, dispersed into the unknown territories of the Lake Chad Basin area. With the drying up of the Lake Chad and the resultant famine and drought, enormous socio-economic tension make the region quite susceptible to extremist anti-state rhetoric. Conclusion

Clearly, while the political and security terrain in West Africa has not been all gloomy, the threat to lives, property and regional peace is imminent. To relevant governments, agencies and other institutions in the above countries and locations (and to all other actors), it is crucial to note that threats to the peace, threats to peaceful governance and threats to lives and property in Africa (and elsewhere) cannot and must not be understood in simplistic binary terms. Each of the above situations and cases point to the interplay of at least two or more factors including the historical, the geopolitical, the socio-economic and the ideological. There are also local as well as global factors. Thus, a variegated long-term plan—involving both hard and soft utilisation of state authority, the empowerment of local peoples, institutions and resources, and taking account of the multiple variables and levels of political realities in these locations—remains the surest way of keeping the peace in these regions and or preventing deteriorating security/political conditions. Muhammad Dan Suleiman is a security expert and political analyst based at the University of Western Australia, Perth. He is completing a PhD on Islamism in West Africa, and he has published articles, policy briefs and opinions on African security, politics and society in academic journals as well as in policy and research institutions and think tanks in Africa, Australia and Asia. He can be contacted at [email protected] or on Twitter: @MDanSuleiman

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

Copyright © 2023 The Zambakari Advisory - Privacy Policy

Our site uses cookies to improve your experience. You can control cookies by adjusting your browser or device settings.

If you continue without changing your settings, we assume that you are happy to receive all cookies.

If not, please feel free to opt out here.

SEO by Qasim Khilji

Our site uses cookies to improve your experience. You can control cookies by adjusting your browser or device settings.

If you continue without changing your settings, we assume that you are happy to receive all cookies.

If not, please feel free to opt out here.

SEO by Qasim Khilji